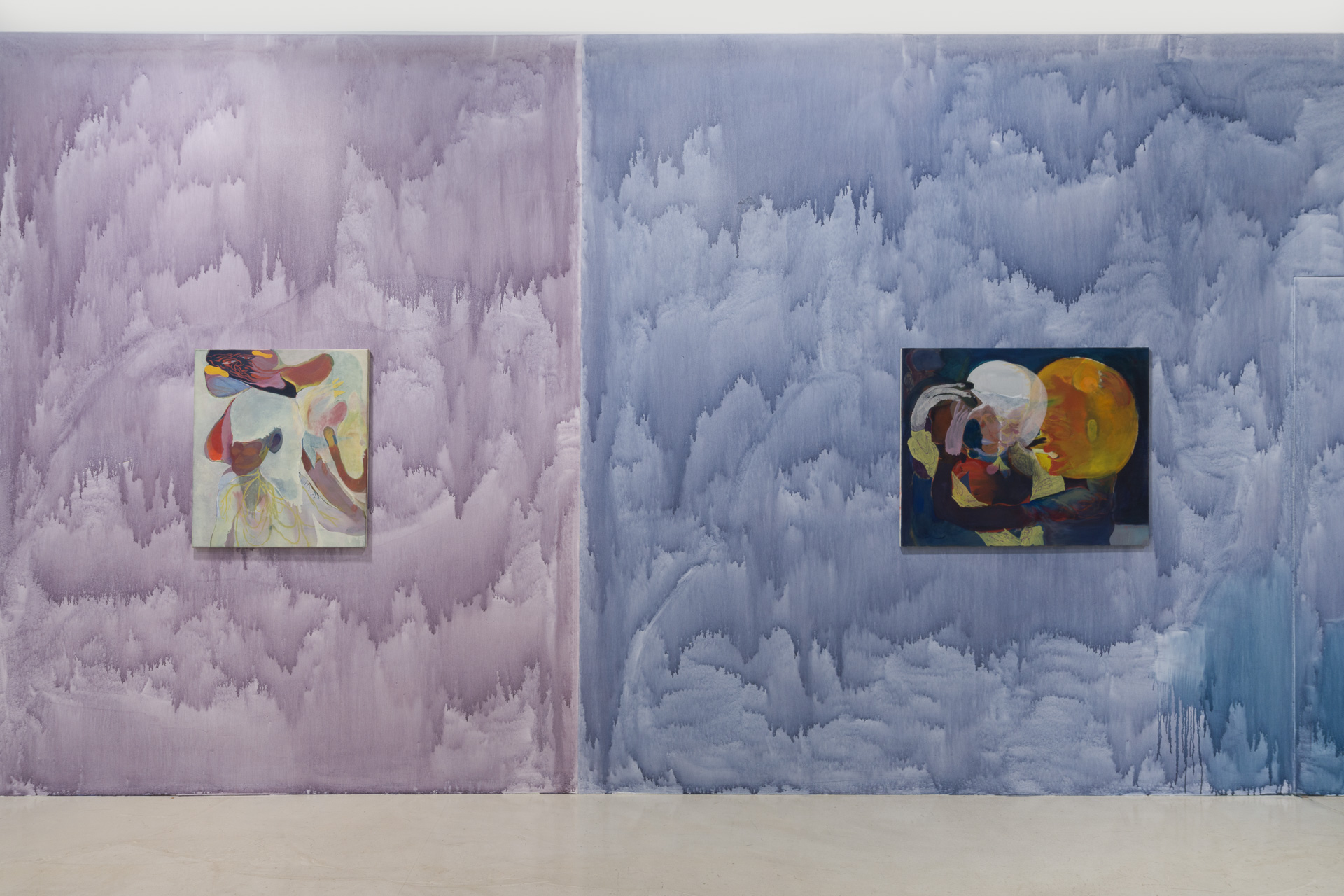

Daniel Domig | Stranger Family

Solo Exhibition, Chalk Horse Gallery, Sydney, Australia

‘Sacred need not mean inerrant; it is enough for the sacred to be inexhaustible’

Rachel Adler, ‘In Your Blood, Live’

‘Abjection is elaborated through a failure to recognise its kin; nothing is familiar, not even the shadow of a memory. I imagine a child who was swallowed up his parents too soon and, to save himself, rejects and throws up everything that is given to him, all gifts, all objects.’ —

Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror

Nothing is as strange as what is closest to us, most familiar. Family is intimacy; family is horror. Family is so close to us that we cannot see ourselves apart from it; family is where we encounter ourselves made strange, unknowable, alien. Family is where we are made, and where we are undone. Family is the womb of the world; the factory of the person. Family is sharp distinctions: public/private, masculine/feminine, reason/emotion, mine/yours. But at the heart of the family we find ourselves undone, uncertain, held too tightly or too little.

For Christian theology, only God creates out of nothing. The rest of us begin in the middle: in the formless chaos of the ocean, the waters of life. The rest of us begin with the division of flesh from flesh, land from sea, slipping or tearing our way out of the dark matrix from which we took our already-forgotten origin. To begin in the middle is to begin with separation. This word and not that. A line here and not there. You and not me. To begin is to mark ourselves off from what surrounds us and to find ourselves longing ever after for a return to the oceanic, the unknown, the ungraspable and indivisible. To begin is to find ourselves already deciding, already decided, already split apart, pinned down, cut off, marked out by language, by names, by kinship.

Western notions of both self and family are organised around the idea of private property, the idea that we can relate both to our own selves and to those around us as though we are objects which can be possessed and exchanged, commodities which can be clearly defined and counted. To be a person has come to mean knowing where we end and the rest of the world begins, being in control of what happens to us and of what we do, impenetrability, mastery. But this notion of personhood is, at best, a late and fragile achievement for us, something potentially within our reach only if we can find a way to mark out the borders of our bodies which begin in indistinction, in the slippery, viscous, visceral confusion of our original gestation. It’s not clear when we become distinct from the bodies which bear us, when a limb becomes ours; unlike other animals it takes for us days and months and years of struggle with and against our bodies and those around us before we can live in any way apart from dependence, can stand in any sense on our own two feet.

Birth, death, sex, and horror all bring us back to the murky, slippery world before we knew ourselves as selves, to the irretrievable origin of creation and destruction, where the holy and the profane, the sacred and the abject meet and mingle.

Most of the time we would prefer not to think too hard about the dark and unsettling indistinction which lies at the heart of our selves, our homes, and our families. To attend too closely is to face down horror, the terrible confrontation with that which is in us more than ourselves, that which is unknowable, unnameable, ungraspable at the heart of our being. To move too close is to know the pleasures of indistinction and of desire, waking up with a foot in your face though you don’t know whose, the warmth of a limb pressed up against you which might be your own or someone else’s. Family life is everyday abjection, the ordinary rhythms of ingestion and excretion, the mundane horror of being no longer merely one’s own – like all acts of formation, a perpetually failed creation.

To be born is always to be born into, to speak always to answer, to make always to respond. We can neither know nor escape what we inherit, cannot choose or reject what is handed over and passed down to us. To run away is also a relation. We cannot cleanse ourselves in the waters of creation, already full of the blood and dirt of life and death, but perhaps here we can unmake ourselves a little, can breathe and drink and swallow in what gathers together; here at the meeting of the rivers of milk and honey, oil and wine; here where we come together and apart, over and again, without beginning or end.

Marika Rose, 2023

Installation views photographed by Simon Larsen

Installation Views